River History

Geology and Prehistory

The rocks which underlie the Calder catchment were formed around 310 million years ago in the Upper Carboniferous period. On the high Pennines, the rocks are mostly millstone grit, consisting of sandstones and mudstones. To the east of Halifax and around the western extreme of the catchment at Todmorden, we see younger coal measures, where coal seams can be found among the mudstones. These rocks were laid down by the actions of rivers ebbing and flowing millions of years ago, depositing silt and sand particles in thick layers when the rivers slowed down, and thinner layers when the flow was faster. Clay particles settling in lakes and swamps between the rivers created the mudstones. In the warm and wet climate of Britain 310 million years ago, the area which is now Calderdale would have been covered in a lush tropical rainforest. Dead plant material falling into the swampy ground gradually decayed and became buried by mud and sand as the rivers changed course over time. As more and more deposits were laid down, the water, oxygen and hydrogen were driven out under immense pressure, leaving only the carbon which formed the coal seams we see today.

These mudstone and sandstone layers are slippery, and soft. The action of the rivers on these soft layers over several millions of years has carved out the steep sided valleys characteristic of the Calder catchment. Because of the slippery layers of rock, landslides are common, and this has shaped the way that the valleys of the Calder and its tributaries look today.

Early Settlement

The place names around the Calder Catchment can tell us about the early landscape and the people who inhabited the area thousands of years ago. Like many English river names, the name of the Calder itself is probably one of the only remnants of the Old Celtic language left in the landscape. The name ‘Calder’ means ‘hard water’ or ‘rapid stream’, suggesting a rocky, fast-flowing watercourse. Similarly, ‘Colne’ comes from the Old Celtic word for stony river.

The place names in the Calder catchment tell us about the different groups of people who lived there. We can see evidence of Roman settlement in Castleford (the ford by the Roman fort). Lots of place names have Old English roots, like Mytholmroyd (the clearing at the river mouths), or Holmfirth (sparse woodland associated with the River Holme), which come from Anglo-Saxon settlers who arrived in the area around the fifth century. Later Viking settlement is shown in names like Ravensthorpe (outlying farmstead or hamlet of a man called Hrafn) or Slaithwaite (clearing where timber was felled). These names, and others ending -thorpe or -thwaite come from the Old Norse language.

Place names also capture some of the people and the activities which were going on on the banks of the Calder, Colne and Holme over a thousand years ago. Place names often refer to the owners of farmsteads or enclosures. Guthleikr or Guthlaugr the Viking had a hill pasture at Golcar, while an Anglo Saxon man named Totta held land around what is now Todmorden. Other names tell us about timber clearance, cultivation, building enclosures and farmsteads, about the species which found habitats: rose hips and brambles, and woodcocks, and about the land itself: stony ground, high ground, valleys and mud all feature in Calder catchment place names.

Calder Valley

Todmorden – ‘Boundary valley of a man called Totta’ (Old English)

Hebden Bridge – Bridge over Hebden water (Hebden from Old English ‘valley where rose hips or brambles grow’)

Mytholmroyd – ‘Clearing at the river mouths’ (Old English)

Luddenden – ‘Valley of the loud stream’ (Old English)

Elland – ‘Cultivated land or estate by the river’ (Old English)

Cromwell Bottom – ‘Crooked stream’ (Old English)

Brighouse – ‘Houses by the bridge’ (Old English)

Mirfield – ‘Pleasant open land’ or ‘open land where festivities are held’ (Old English)

Lower Hopton – ‘Farmstead in a small enclosed valley or enclosed plot of land’ (Old English)

Ravensthorpe – ‘Outlying farmstead or hamlet of a man called Hrafn’ (Old Scandinavian)

Dewsbury – ‘Stronghold of a man called Dewi’ (Old Welsh personal name + Old English)

Horbury Bridge – ‘The bridge by the stronghold on muddy land’ (Old English)

Stanley – ‘Stony woodland or clearing’ (Old English)

Castleford – ‘Ford by the Roman fort’ (Old English)

Colne Valley

Marsden – ‘Boundary valley’ (Old English)

Slaithwaite – ‘Clearing where timber was felled’ (Old Scandinavian)

Golcar – ‘Shieling or hill pasture belonging to a man called Guthleikr or Guthlaugr’ (Old Scandinavian)

Holme Valley

Holmbridge – ‘Bridge over the River Holme’

Holmfirth – ‘Sparse woodland associated with the River Holme’ (Old English)

Honley – ‘Woodland clearing where woodcock abound’ or ‘woodland clearing where there are stones and rocks’ (Old English)

Industry

Industry has been hugely influential in shaping Calderdale. One of the very earliest fulling mills in the country, carrying out a process in which fibres are cleaned and beaten to make them softer, stronger, and better for use in cloth making, was built at Sowerby Bridge in around 1290. Calderdale clothmakers specialised in a type of cloth called ‘Kersey’, which was known for being hard-wearing and good value. By 1475, the Calderdale area had become the largest producer of this type of cloth in England. Cloth production was so integral to the economy in the vicinity of Halifax that a special statute of 1555 allowed small wool dealers and middlemen to continue to work in their own homes in the area, bringing small, individual consignments of wool to clothing makers in the towns and villages on their own backs, even as the practice was banned elsewhere by an earlier statute of 1552.

From the late eighteenth century, improved transport links led to an explosion in the cloth industry, and in the population of towns like Halifax, bringing employment and jobs into the region. As Daniel Defoe wrote, in 1724, ‘”…and so nearer we came to Halifax we found the houses thicker and the villages greater…if we knocked at the door of any of the master manufacturers we presently saw a house full of lusty fellows, some at the dye vat, some dressing the cloth, some in the loom.’

This began to change in the nineteenth century, as the hand loom and system of home working began to be replaced by large scale mills and factories. Many woollen workers believed that rights bestowed on them by Tudor law would protect them in the face of this change, but petitions by factory owners led to Parliamentary Select Committee investigations in 1803 and 1806, and the eventual repeal of the Tudor laws in 1809, paving the way for large scale factory-based industry in Calderdale. The fast flow of the River Calder made it ideal for powering mills, and weirs were used to control both flow and depth to ensure that waterwheels to drive the mill machinery could be kept running. This facilitated the beginning of Calderdale’s tradition of cloth making on an industrial scale.

Nineteenth century industrialisation also saw the creation of further improvements to transport for trade, in the form of the canal system. This was also a period characterised by change within the rivers themselves. Advances in technology saw ever more powerful milling machinery being driven by the water, controlled and directed by dams, weirs, sluices and gates. This was followed by the introduction of steam. Powering larger mills on the more accessible valley floor, steam technology tended to leave villages higher up the valley sides stranded, as sources of employment moved lower down the hills. This has given us many of the mill and factory buildings, and workers’ cottages which characterise the countryside around the River Calder today, and had a dramatic impact on living conditions for many Calder valley workers. Small, cramped accommodation for rapidly expanding populations of working people was hastily put up, leading to the problems of unhygienic conditions, lack of light, lack of access to clean water, and rapid spread of disease associated with back to back housing, open sewers and occupancy by multiple families, leading to some having their only home in cellar rooms.

The need for clean water for these rapidly growing communities led to the construction of reservoirs in the hills, and reformers began work on model villages which tackled some of the more serious deprivations of living in industrial communities. The provision of mains water and drainage allowed newer factories to be built higher up in the valley, away from the crowded conditions close to the valley floor.

This nineteenth century industrial activity largely laid out the landscape of Calderdale as we see it today.

Transport

The expansion of industry in Calderdale was supported by the creation of a series of turnpike roads along the valley bottom. These replaced the hillside packhorse tracks, and dramatically reduced the travel time between the Calderdale sheep farms, mills and major commercial centres. Perhaps the greatest innovation and agent for change in Calderdale’s landscape, water management, and connection to the wider world came in 1770 with the completion of the Calder and Hebble Navigation. Following the completion of the initial navigation, further cuts and sections were opened: the Salterhebble branch in 1828, and the Rochdale Canal in 1804. Joseph Priestley’s Historical Account of the Navigable Rivers, Canals and Railways of Great Britain, published in 1831 described the changes to Calderdale brought by the canal system:

The country through which it passes has also partaken of the great advantages arising from a well regulated navigation. Agricultural lime has, by its means, been carried to fertilize a sterile and mountainous district; stone and flag quarries have been opened in its vicinity, which have furnished inexhaustible supplies for the London Market, and other parts of the kingdom; we allude, in particular, to the celebrated flag quarries of Cromwell Bottom and Elland Edge, at the former of which there is an extensive wharf, Iron-stone and coal works have been, and continue to be, extensively worked on its banks.

The canal continued to be used commercially until 1981, having undergone numerous new cuts, weir bypasses, and new lock constructions over the course of its two hundred year history.

Flood History

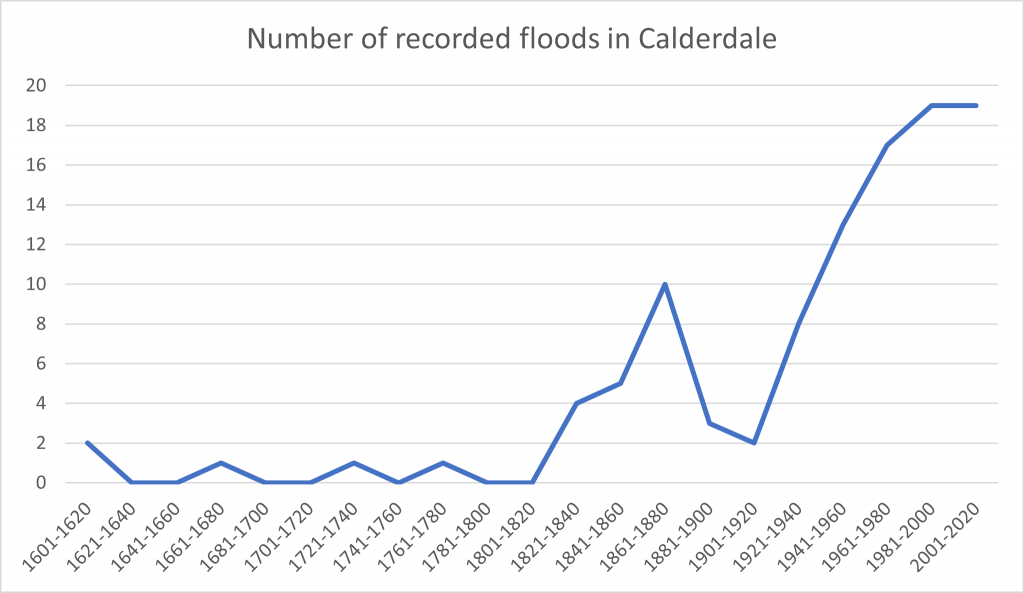

Calderdale and the surrounding areas have been shaped by flooding. The steep, narrow valleys mean that this has always been a risk. The earliest flood on record in Calderdale occurred in 1615, and destroyed Elland Bridge. The wooden bridge at Elland had been replaced by stone in the fourteenth century as it had been repeatedly swept away by flooding. This stone bridge had to be rebuilt again in 1617.

From 1830 to 1895, twenty two serious floods were recorded in Calderdale. This is likely to be evidence of better record keeping rather than an increase in flood events, but it might also reflect an increase in industrial buildings and related changes in and around the river, like straightening and walling in the channel. In 1837, the flooding in Hebden Bridge reached nine feet in places, with the river water flooding into the canal as it was slowed downstream of the town by the canal viaduct at Black Pit.

Almost twenty years later, in 1855, “Todmorden was visited by one of the largest floods within the recollection of the oldest inhabitants.” At Mytholm the water rose to the same height as in the flood of 1837, causing serious damage to Green’s Mill, Portsmouth, and a joiner’s shop at Gauxholme was “swum away.”

The 1860s have been described as a decade ‘in which it never stopped raining,’ causing numerous floods throughout the Calder valley, including one, in 1866, which was second only to that of 1775 in height.

Severe flooding continued throughout the rest of the nineteenth century. The first two decades of the twentieth century were not marked by reports of severe flooding, but flooding resumed in the 1920s, when it was noted that the Calder was prone to flood every ten years.

In September 1946, in the aftermath of World War Two, Calderdale saw a flood which has been described as Mytholmroyd’s worst flood until that of Boxing Day 2015. Downstream, the flooding in Sowerby Bridge reached 21 inches higher than 1866, while 354 properties in Mytholmroyd were flooded up to five or six feet deep. From Brighouse to Todmorden, 905 properties were affected. This must have come as a bitter blow after the deprivations of war, with rationing still in full force.

Floods in the second half of the twentieth century are better recorded, and we can see from the records that minor flooding occurs at least once almost every year somewhere in Calderdale. This is variously due to rainfall, snow melt, overflowing drains and blocked culverts.

The twenty-first century has seen several major flood incidents in Calderdale, including severe flooding in 2000, 2012 and 2015, which saw record high water levels, and an unprecedented number of homes and businesses inundated. Similar devastation was seen again following Storm Ciara in 2020, which damaged at least 695 homes and 572 businesses, as well as roads, bridges and infrastructure.

The series of three severe floods in 2012 prompted the formation of a Calderdale Flood Recovery and Resilience Programme, bringing together a range of partners from across the water and environment sectors to build resilience and reduce the impact of flooding in Calderdale.

Since 2016, there has been a Calderdale Flood Action Plan, created by the Environment Agency on behalf of the Calderdale Flood Recovery and Resilience Programme. This has incorporated Flood Risk Reduction Schemes, Natural Flood Management schemes, and Flood Alleviation Schemes at Mytholmroyd, Hebden Bridge, and Brighouse.

References

Eye on Calderdale, History of Flooding in Calderdale https://eyeoncalderdale.com/history-of-flooding-in-calderdale

From Weaver to Web: Online Visual Archive of Calderdale History, https://www.calderdale.gov.uk/wtw/index.html; https://www.calderdale.gov.uk/wtw/timeline/timeline.html

J.S. Lee, The Medieval Clothier (Boydell & Brewer; Boydell Press, 2018).

A.D. Mills, Oxford Dictionary of British Place Names (1991, Oxford, 2003).

Nicholson Guide, North West & the Pennines (Harper Collins Publishers, 2006).

J. Priestley, Historical Account of the Navigable Rivers, Canals and Railways of Great Britain (1831).

West Yorkshire Geology Trust, Geology of Calderdale, https://www.wyorksgeologytrust.org/misc/Geology%20of%20Calderdale.pdf [viewed 26.03.2021]

Subscriber for newsletter

To get the latest news from us please subscribe your email.